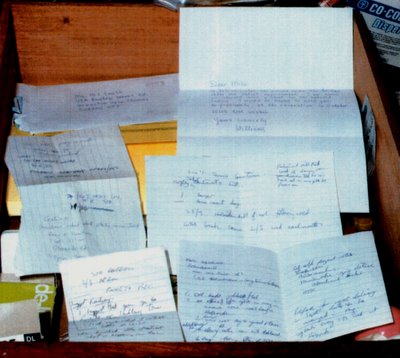

It did not strike me as odd at the time, but I should have been suspicious why the man who handed me £20,000 in cash was doing so in brand new £50 notes. As you can see from the picture below, this money was paid in crisp notes, straight from the bank, and the hard shiny paper almost crackled as it was handled.

Money found at my home

I suppose I should have asked some questions about this money, but then I expect I just thought - well, ‘money is simply money’ - right? I guess not, as this stuff was just too clean, and it might cause a few problems … it could look like the ink wasn’t quite dry on the paper, and the notes were so new they almost looked like forgeries.

This is where a bit of money laundering would have come in useful. With a washing machine, and a suitable detergent, it should have been possible to age the money to make it look a little more used. A good fabric conditioner would have made the notes softer to handle, and added a fresh herbal smell to disguise that unmistakable new paper odour.

I didn’t think, at the time I was given this money: ‘where did it had come from?’ If this was “dirty” money, then it certainly looked pretty clean to me. At the time of my arrest I was found in possession of £2,150 in £50 notes: the two batches of £1,000 were in two separate manila envelopes, shown at the top of the photograph, and I also had three £50 notes in the pocket of the jeans I was wearing when I was arrested.

During my police interviews, Detective Chief Superintendent Malcolm MacLeod said the money was found to be in one continuous set of serial numbers, but that was not true and a ploy he had used to try to unsettle me. It was actually in several batches and single serial numbers.

The serial numbers on the 43 £50 notes were as follows:

B19 402054

B60 047506

C03 879560

C26 000800

D03 699453 + 6

D25 231111

D27 315283 + 5 + 6 + 7 + 8

D27 849166 + 7 + 8

D27 849173 + 4 + 5 + 6 + 7 + 8 + 9

D27 849182 + 3 + 4

D28 908537 + 8 + 9

D28 908541 + 2

D40 578780

D42 595622 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 + 7 + 8 + 9 + 30

D57 805931

D57 805937 + 8

Detective Constable Jonathan Peter Say looked into the source of this money, and he came to the conclusion that none of the notes were issued from the Bank of England prior to 6 June 1990. Apparently not all of the notes were investigated, but the following information was obtained from the Bank of England and the relevant banks that were issued with the notes.

Notes serial D27 315*** were issued in parcel No. C34783 to National Westminster Bank PLC on 21 November 1990. Mr. Michael Keith Robinson (of National Westminster Bank) said these were new £50 notes, which were dispersed to various NatWest branches in the North Yorkshire area. No records were kept of which branches received the notes.

Notes serial D27 849*** were issued in parcel No. C27172 to Republic National Bank of New York on 9 July 1990. Notes serial D42 595*** were issued in parcel No. C43494, and were also sent to Republic National Bank of New York, on 12 December 1990. Mr. Stephen John Allen (of the Republic National Bank of New York) said these were brand new £50 notes, and they would have been dispatched to their banking clients in various European cities, and perhaps London, but no records were kept of where they were sent.

Notes serial D03 699*** were issued in parcel No. C20988 to Barclays Bank PLC on 6 June 1990. Notes serial D28 908*** were issued in parcel No. C27536 to Barclays Bank PLC on 19 July 1990. Mr. Peter H. Titchmarsh (of Barclays Bank) said these were new £50 notes, and each consignment included £2.5 million in new £50 notes. Again no records were kept of which destinations the parcels of money were sent to.

Notes serial D57 805*** were issued in parcel No. C51632 to TSB Bank PLC on 30 July 1991. Mr. John Anthony Jackson (of TSB Bank) said these were new £50 notes and the container remained sealed until 14 August 1991. The notes were distributed over much of South England until the container was exhausted on 18 September 1991. Again - you guessed it - no records were kept of which branches received which parcels of notes.

So, according to what was found, it would appear that the traceability of the £50 notes was fine up until the point at which it was distributed to individual branches or customers, but then it became untraceable. This was a very convenient outcome for the police and the prosecution at my trial, as they could simply say it was KGB money and there was no evidence to prove otherwise. In fact, hardly any evidence was produced about the money at all, and at my trial this issue was almost brushed aside as insignificant. Where the money had originated from, and who had withdrawn it from a particular bank, therefore was not something that particularly bothered the prosecution, but the jury were told it had come from the KGB. On reflection this now seems a little sinister.

Why, for example, were no witnesses called to testify about the money and the problems of tracing it? As the prosecution case was so clearly that this money had come directly from either a KGB source, or at least a Russian source, then it was surprising that the source of the money was given so little attention.

This matter is linked to my suspicion that the organisation behind my entrapment and arrest was not the KGB at all, but rather MI5 or Special Branch. If the money had been withdrawn from banks by members of these British organisations, then obviously they would not wish that fact to become known at my trial, otherwise that would severely weaken the Crown’s case that the KGB were involved at all.

This argument - whether the money was “clean” or “dirty” - has been lost amongst the mass of other evidence put at my trial, and documented in the many pages and volumes of dull statements, exhibits and transcripts. However, it is still an important issue to consider, and it makes one wonder about the truth behind that money’s origin.

From the reports of the police’s investigations, and the case put at court, the Crown argument was that I had used much of the money to purchase £10,000 worth of computer music equipment from The Synthesizer Company (TSC), as a large portion of the cost had been paid in cash.

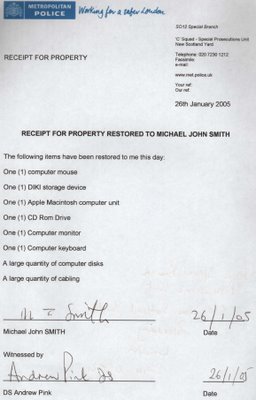

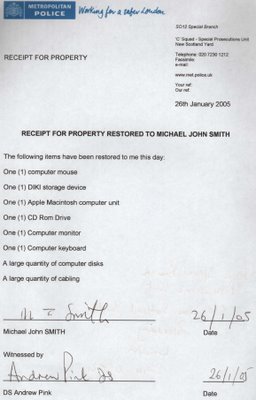

It is strange, therefore, after much pressure from me, that the police finally returned all my computer equipment to me on 26 January 2005. See the receipt I signed below.

Police receipt for computer equipment

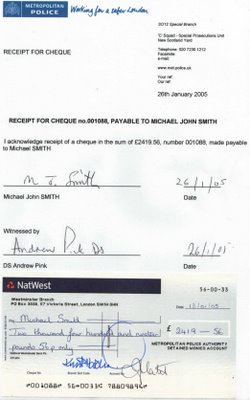

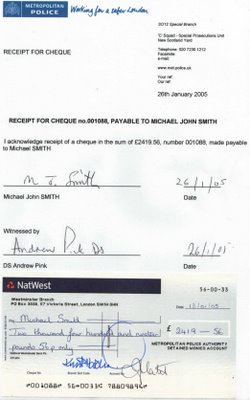

Although I never asked for the return of the money, it is even stranger that on the same day the police also returned the money (shown in the photograph) plus interest. If the police believed this money had come from the KGB in payment for criminal activity, then why did they return it to me? See the receipt for that below.

Police receipt and cheque for money

The only quibble I have is that they did not pay a market rate of interest on the money, and I would have been better off investing it in the stock market, or some other more lucrative venture.