Bold expansion in tourism

Prepare for culture shock in the Acapulco of the eastern hemisphere. Adrienne Keith Cohen, Travel Editor, has been there

Lord Wrongfont, last occupant of the British Residency. His statue in Guttenberg Square, Bodoni, has been carefully maintained by succeeding administrations.

You must be up betimes to see San Serriffe’s truly unique attraction. This is the flotilla of lighters that travel overnight, seven nights a week, from the east coasts of these neglected equatorial islands arriving in their dozens at dawn to unload their cargo at the West coast tourist resorts of Cap Em, Garamondo, Villa Pica, and Gillcameo.

The wise visitor, however, will watch this spectacle from a safe distance - and preferably from behind glass. The expanded Century Hotel at Gillcameo is ideally situated for this purpose, every room facing the Atlantic shoreline, vast windows offering an uninterrupted view of this daily ritual - not to mention the necessary protection.

For the cargo that is unloaded with such ceremony each morning is the sand eroded the previous day from the west coast beaches by tidal currents and dumped without so much as by your leave along the less developed east coasts of this extraordinary archipelago.

No islands in the world can surely claim a greater population mix than San Serriffe. Just stroll through Bodoni, the capital, and one minute you will be confronted by a vast church, extravagantly decorated in the Portuguese Manuelline style, the next you may well find yourself in an Arab souk. With luck (or a good guide) you can manage to take the exit from the bazaar that is guarded by an ancient Spanish fort, its walls shored up in the nick of time by a team of visiting conservationists.

In the country where the population of 1,782,000 consists of Europeans and mixed races, Flongs, Creoles, Malaysians, Arabs, plus a leavening of Chinese, it seems only right and proper that it should have been an international expedition that managed to preserve so much evidence of the improbable history of these islands.

Spanish, Portuguese, and British by turn, they became independent in 1967. The usual upheavals followed until the current President, General Pica, restored peace and guaranteed prosperity almost overnight by declaring the islands a tax haven in which all and any foreign capital would be welcome.

The result constitutes a fair degree of culture shock, from a network of motorways that make North American turnpikes and freeways look like so many country lanes, to two international airports. San Serriffe Airways, who already operate scheduled services to the capital, Bodoni, Upper Caisse, northernmost of the two biggest islands, are also planning to operate to its southern neighbour, Lower Caisse, in the near future.

Until recently, the islands have mainly attracted business travellers - and the potential of Bodoni as an international convention and artistic centre has been seized to remarkable effect (the new trade centre, due for completion this year, and the splendid modern theatre are both British enterprises).

But it is Lower Caisse, separated from its northerly neighbour by the formidable Shoals of Adze, that offers the rosiest tourist prospects. Gillsands, stretching down for miles from the southernmost resort of Gillcameo, could well become a second Acapulco once a solution is found to the problem of sand erosion.

One of the many beaches from which terrorism has been virtually eliminated

Meanwhile, comfortable, modern air-conditioned hotels all have the statutory swimming pool - not to mention poolside bars and “coffee shops,” the latter serving Creole delicacies as well as the inevitable steaks, hamburgers and fried chicken.

Food, indeed, must be accounted one of the major pleasures on the islands - particularly as the wines to accompany them are duty-free. Spanish and Portuguese wines still predominate, though Joe’s Diner, on the Garamondo side of Villa Pica, has a cellar-full of French vintages as improbable as the name of this highly sophisticated restaurant.

Although the hinterland is still largely swamp, malaria has been almost eradicated, and the Highway General Pica drives through from the coast to the treacherous Woj of Tipe. This effectively serves as a border between the rest of the island and the habitat of the Flongs.

Isolationist by nature, this ancient, aboriginal race is only slowly being allowed to receive tourists with the same courtesy and warmth as the rest of their countrymen. For the time being, however, permits to enter their territory must first be obtained from the District Commissioner’s Office. You’ll need a plausible story to get there - not to mention a strong constitution with which to confront the unmade tracks you hit with a bump when the motorway suddenly gives out.

A statue of the President, General M.-J. Pica, to be unveiled today in Cloister Gardens, Bodoni, as part of the celebrations of ten years’ independence.

Transposed by the tides

San Serriffe is on a collision course with Sri Lanka, but Britain and the EEC could benefit from its underwater research. Anthony Tucker, Science Correspondent, explains

Diagram showing how the seasonal reversal of the main oceanic current affects the erosion and deposition patterns at the extremes of the tidal cycle. (By courtesy of the Institute of Indian Ocean Marine Sciences.)

The extraordinary eastward movement of the San Serriffe island group was first observed, accidentally, by Sir Charles Clarendon, after whom the port is named, during an exploration of the Indian Ocean in 1796. Sailing north in his schooner Excelsior he became stranded on a sand Spit east of the islands on March 13 - a date which he underlined in his log.

Since only two years earlier Captain Meriwether Lewis, one of Cook’s original crew (who later became Governor of Louisiana and was one of the most able cartographers of his time), had recorded that the waters east of the islands offered a clear passage, Sir Charles decided to anchor and investigate as soon as Excelsior lifted off with the tide.

It happened that Sir Charles, although a botanist and mineralogist, was also the author of the empirical hypothesis which explains why large pebbles rise and successively finer particles fall in sedimentary systems. He had arrived at his explanation (which proved on further investigation to be false) through direct observation of erosion of the Channel coast near Rye.

He was therefore able to study the San Serriffe phenomenon in a comparative way and his diary for 1796, now at the Geographical Society at Kensington Gore, contains the first description of the extraordinary scouring and deposition pattern which continually shapes and reshapes the island group.

Sir Charles, however, saw only a part of the process when, during the spring tides, the spit of sand on which he had stranded and which was visible at its western extremity as a sand bank between the islands, was swept away. Sir Charles believed that this reformed further offshore creating an ever-extending underwater hazard, and it is clear from his notes that he realised that the material was somehow accreting from the western shores. “The land is being eaten bye the see,” he wrote, and “raising hazardes to the Island Easte. In these wateres keep the islands to starboard when heading northe.”

Almost a century passed before this simple explanation was challenged and corrected. An expedition from the Royal Society - one of the earliest in the series of which the present Aldabra Expedition is the most recent - landed in 1886 to study the habitat. The loss of one of the expedition’s two huts, set up on the western shore of the S. Island as a laboratory and store, drew sharp attention to the erosion problem. Systematic studies were made and the expedition brought back the first description of the complete repetitive cycle of erosion and deposition.

Linked intimately with the multiple tide system of the double island formation, with the biennial reversal of the main current flowing parallel to the East coast, and with an effect not understood by the Royal Society expedition but now known as a “double Coanda,” the scouring and deposition has two alternating major phases.

In one, during the neap tides, material is carried from the western shores of both islands and deposited in the form of a sandbank and spit which almost closes the strait between the islands, known as the Shoals of Adze, at low water and which reaches out eastward for about 1,000 metres. Deposition in this position depends on the existence of the remnants of an earlier spit, and on the fingers of material reaching out from both islands into the strait which result from the reverse flow patterns during neaps.

With the spring tides the reduced channel width between the islands leads to very high flow rates. Since the main water flow during these phases is southward the material now being scoured rapidly from the bank and spit is deposited in different ways on the north and south islands.

Deposition on the northern island falls uniformly on the eastward semicircular shore, while the stronger southerly movement draws out the deposition pattern on the southern island and accounts for the curious “tail” which has developed over the centuries.

But the phenomenon unique to San Serriffe, as far as is known, is that as the bank and spit erodes two or three “herring bone” fingers are left reaching out partially across the strait. These are undoubtedly due to the creation of standing waves during the fast erosion phase, but if they did not occur accretion on the eastern shore could not take place and the islands would have disappeared long ago.

As it is the islands are in a quasi-stable state, but moving steadily eastward. Because the scour and deposition rate changes as the cube of current velocity, the islands will accelerate at first gently and then more rapidly as they approach Sri Lanka. Simple calculations based on the present movement of 1,400 metres a year and an exponential acceleration rate suggest that the island group will hit the coast of Sri Lanka at a velocity of 940 km an hour on January 3, 2011.

In spite of the difficulty of the waters around the islands, and the shifting hazards, a British gravel dredging company last year put forward the proposition that, by normal dredging procedures, it should be possible to stabilise the land masses long enough for proper surveys to be carried out. This proposal is believed to be under serious study by both the Department of Industry and the so-called Rockall Group at the Foreign Office.

In the meantime, basing his calculations on the most recent observations at San Serriffe and on the Institute of Marine Sciences computer model of the Channel, Dr. John Funditor, of Imperial College, has put forward a daring scheme.

This is to create a double Coanda island group in the English Channel where, according to Dr Funditor, the current patterns would lead, not to an island movement but to the gradual building up of a Channel barrage. This would have immediate and obvious benefits.

There would be a direct road and rail link between Britain and the EEC mainland; the barrage would become the major Europort, accepting traffic from either east or west and would entirely eliminate the present Channel shipping traffic problems; the argument about the Chunell would be silenced, and there would be a permanent reduction in the sea level of the North Sea. This last effect would be most important because if would reduce the costs of North Sea coast protection, reduce the risk of flooding, eliminate the need for a Thames barrage and make the arduous task of oil production a little easier.

It may well turn out that advantages such as these, likely to be ignored in Britain, will be grasped by the Asian countries towards whom San Serriffe is moving. One fear, already being expressed in Karachi, is that as soon as the islands enter an economic zone as defined by the Law of the Sea, then its unique water flow pattern will be deliberately disrupted by an annexing state to prevent it moving out again. Since this could, however, destroy the islands completely, the view in both London and Washington is that this remarkable natural phenomenon should be allowed to run its full course.

Eric Dymock reveals a major triumph for motor sport in the islands

Since only two years earlier Captain Meriwether Lewis, one of Cook’s original crew (who later became Governor of Louisiana and was one of the most able cartographers of his time), had recorded that the waters east of the islands offered a clear passage, Sir Charles decided to anchor and investigate as soon as Excelsior lifted off with the tide.

It happened that Sir Charles, although a botanist and mineralogist, was also the author of the empirical hypothesis which explains why large pebbles rise and successively finer particles fall in sedimentary systems. He had arrived at his explanation (which proved on further investigation to be false) through direct observation of erosion of the Channel coast near Rye.

He was therefore able to study the San Serriffe phenomenon in a comparative way and his diary for 1796, now at the Geographical Society at Kensington Gore, contains the first description of the extraordinary scouring and deposition pattern which continually shapes and reshapes the island group.

Sir Charles, however, saw only a part of the process when, during the spring tides, the spit of sand on which he had stranded and which was visible at its western extremity as a sand bank between the islands, was swept away. Sir Charles believed that this reformed further offshore creating an ever-extending underwater hazard, and it is clear from his notes that he realised that the material was somehow accreting from the western shores. “The land is being eaten bye the see,” he wrote, and “raising hazardes to the Island Easte. In these wateres keep the islands to starboard when heading northe.”

Almost a century passed before this simple explanation was challenged and corrected. An expedition from the Royal Society - one of the earliest in the series of which the present Aldabra Expedition is the most recent - landed in 1886 to study the habitat. The loss of one of the expedition’s two huts, set up on the western shore of the S. Island as a laboratory and store, drew sharp attention to the erosion problem. Systematic studies were made and the expedition brought back the first description of the complete repetitive cycle of erosion and deposition.

Linked intimately with the multiple tide system of the double island formation, with the biennial reversal of the main current flowing parallel to the East coast, and with an effect not understood by the Royal Society expedition but now known as a “double Coanda,” the scouring and deposition has two alternating major phases.

In one, during the neap tides, material is carried from the western shores of both islands and deposited in the form of a sandbank and spit which almost closes the strait between the islands, known as the Shoals of Adze, at low water and which reaches out eastward for about 1,000 metres. Deposition in this position depends on the existence of the remnants of an earlier spit, and on the fingers of material reaching out from both islands into the strait which result from the reverse flow patterns during neaps.

With the spring tides the reduced channel width between the islands leads to very high flow rates. Since the main water flow during these phases is southward the material now being scoured rapidly from the bank and spit is deposited in different ways on the north and south islands.

Deposition on the northern island falls uniformly on the eastward semicircular shore, while the stronger southerly movement draws out the deposition pattern on the southern island and accounts for the curious “tail” which has developed over the centuries.

But the phenomenon unique to San Serriffe, as far as is known, is that as the bank and spit erodes two or three “herring bone” fingers are left reaching out partially across the strait. These are undoubtedly due to the creation of standing waves during the fast erosion phase, but if they did not occur accretion on the eastern shore could not take place and the islands would have disappeared long ago.

As it is the islands are in a quasi-stable state, but moving steadily eastward. Because the scour and deposition rate changes as the cube of current velocity, the islands will accelerate at first gently and then more rapidly as they approach Sri Lanka. Simple calculations based on the present movement of 1,400 metres a year and an exponential acceleration rate suggest that the island group will hit the coast of Sri Lanka at a velocity of 940 km an hour on January 3, 2011.

In spite of the difficulty of the waters around the islands, and the shifting hazards, a British gravel dredging company last year put forward the proposition that, by normal dredging procedures, it should be possible to stabilise the land masses long enough for proper surveys to be carried out. This proposal is believed to be under serious study by both the Department of Industry and the so-called Rockall Group at the Foreign Office.

In the meantime, basing his calculations on the most recent observations at San Serriffe and on the Institute of Marine Sciences computer model of the Channel, Dr. John Funditor, of Imperial College, has put forward a daring scheme.

This is to create a double Coanda island group in the English Channel where, according to Dr Funditor, the current patterns would lead, not to an island movement but to the gradual building up of a Channel barrage. This would have immediate and obvious benefits.

There would be a direct road and rail link between Britain and the EEC mainland; the barrage would become the major Europort, accepting traffic from either east or west and would entirely eliminate the present Channel shipping traffic problems; the argument about the Chunell would be silenced, and there would be a permanent reduction in the sea level of the North Sea. This last effect would be most important because if would reduce the costs of North Sea coast protection, reduce the risk of flooding, eliminate the need for a Thames barrage and make the arduous task of oil production a little easier.

It may well turn out that advantages such as these, likely to be ignored in Britain, will be grasped by the Asian countries towards whom San Serriffe is moving. One fear, already being expressed in Karachi, is that as soon as the islands enter an economic zone as defined by the Law of the Sea, then its unique water flow pattern will be deliberately disrupted by an annexing state to prevent it moving out again. Since this could, however, destroy the islands completely, the view in both London and Washington is that this remarkable natural phenomenon should be allowed to run its full course.

Eric Dymock reveals a major triumph for motor sport in the islands

Garamondo pulls it off

Following meetings between the Formula 1 Constructors’ Association and the Real Automobileclub do San Serriffe, a world championship Grand Prix will take place on the new Autodromo Pedro Venezia at Garamondo next year. A rather hurriedly-organised non-championship event inaugurated the new 2¾-mile track in December, ’76, and the International Automobile Federation has sanctioned a championship date for next February, immediately before the South African Grand Prix at Kyalami.

“We are delighted to have the Grand Prix of San Serriffe on the calendar for next year,” Bernie Ecclestone of the Formula 1 Association said at the formal cheque-signing ceremony earlier this week. “The prize fund will have no more than a marginal effect on the San Serriffe balance of payments. In addition, we are putting up a special prize for the first local driver to finish.”

The most likely recipient of this will be young Manuel Transmizzio who did so well with his Guinness-Martini Ford in last year’s European Formula 2 Championship, and who has been tipped to join the John Player Lotus team before the end of the season.

The new track has been designed by a consortium headed by Jackie Stewart, whose commercial links have been put at the disposal of the RAC do San Serriffe for next year’s event, which he will cover for ABC television in the United States. His interest has resulted in Rolex putting up giant replicas of their Oyster Perpetual wrist watches so that the 100,000 spectators can follow lap times from their seats.

Texaco has financed the construction of the track together with local aperitif manufacturer Pedro Venezia.

Texaco are to sponsor the Grand Prix. All the major teams are expected to enter, on a track planned with safety as its main consideration, unlike the old Circuito Garamondo. Here, as in the well-remembered STP Challenge Trophy races at Kindley Field in Bermuda, a no-passing section had to be included where the narrow track crossed a Bailey Bridge.

The burden of development: A San Serriffian carries his washing machine home from the factory gates - picture by David Housden.

Casting off into unknown wealth

The industrial revolution that has engulfed the tiny Republic within the past ten years may soon result in its challenging the economic power of the West. Victor Keegan, Business Editor, reports.

San Serriffe is creating world-wide interest as an example of a developing country trying to turn itself into an industrial society with the benefits of a large oil discovery.

When oil was first discovered in 1971 the Government set itself a 10-year target to attract new industry to replace its traditional dependence on agriculture and sporadic tourism. When General Pica took over he completely endorsed the 10 Year Plan, though the base year was changed to 1976. Thanks to the quintupling of oil prices in recent years - and sharp rises in the prices of the country’s other raw materials, phosphate and timber - the inhabitants now enjoy the highest per capita income in the world.

General Pica’s Industrial Development Strategy placed emphasis on truck manufacture, textiles, shipbuilding, microelectronics, tourism, a duty free port, conference centres, aluminium smelting, steel, and furniture polishing.

Some of these, like the duty free port and tourism, have been impressive successes. The string of hotels and “appartimentos” along the shifting West coast matches anything in Spain and provides an attractive alternative to Europeans seeking winter sun but bored with the Canaries. The international airport at Bodoni is claimed to be one of the biggest of its kind and was used for the proving flights of Concorde.

An impressive steel works has been built near the deep water terminal at Port Elrod in the North-east capable of producing 400,000 tonnes of crude steel a year. The complex, with an associated rolling mill, was built with the help of technical advice from the British Steel Corporation which is pleased with the end result. Although it produces more steel than is currently consumed on the islands, there are plans to start exporting when the current international recession is over.

About six miles south of Port Elrod the State-owned Industrial Initiative Board has built a medium-sized shipyard capable of building supertankers or bulk carriers. The yard is modelled on the widely praised yards at Bilbao in Northern Spain and was completed in October last year, almost three months ahead of schedule. No orders have yet been received because of the depth of the international recession, but the IIB is confident that a combination of low cost labour and modern facilities will ensure that it gets its fair share of work when orders eventually return to the industry.

By contrast the giant aluminium smelter, nearby, commissioned last summer, is working at 75 per cent capacity. By early 1978 it is expected to be working at 100 per cent of programmed capacity when an associated power station (utilising natural gas which would otherwise be “flared” at sea) is also completed. At present, if the smelter is run nearer full utilisation, it could overload the country’s other power station near Bodoni, and cause power cuts.

The IIB has also been involved in building a plant to assemble Land Rovers which are considered ideal vehicles for San Serriffe’s unpredictable countryside. The new company is able to sell every vehicle it produces, though output has been hampered by a shortage of “knocked down” kits from England.

The IIB, which is the lynchpin of the industrial strategy, has access to £900 millions of oil money over a period of six years. This is more than the gross national product of the islands as recently as four years ago and illustrates the size of the country’s ambitions.

In addition to creating prestigious new industries for the country, the IIB also provides risk capital for the burgeoning entrepreneurial classes of San Serriffe. As Mr Manuel Sinibaldi, President of the IIB puts it: “We are really an ordinary merchant bank which happens to be owned by the Government. We provide funds for soundly based commercial schemes in competition with all the other banks.”

The recently formed Confederation of Serriffe Industry, which is becoming an increasing force in the country’s politics, was loosely structured on the British CBI. Like the CBI its governing body consists of a council of 400 top businessmen. At present there are only 295 people on the council because of the comparatively small size of industry, but the remaining vacancies will be filled as new businessmen come along.

The industrial strategy is closely linked to the Government’s overall economic policy which envisages growth of 10 per cent a year between 1970 and 1980. In spite of the disappointing progress in the first half of the decade, the Economic Department is sticking to its 10-year forecast so the economy is now expected to grow by 20 per cent a year for the rest of the decade. It is pointed out that this could easily happen if all the recently completed projects were working at even 90 per cent of theoretical capacity.

This point, apparently, impressed a team from the British Treasury which went on a fact-finding mission to the islands towards the end of last year to discover if there were any lessons for Britain in San Serriffe’s attempts to change from a developing country with a declining industrial base to a modernised oil-based economy. Although the team did not think there was anything specific they could learn from the particular industries chosen by the San Serriffe Government, they were enormously impressed with the industrial strategy which had succeeded in curing one of the worst infrastructural problems of the economy - high unemployment among civil servants.

The team was also impressed by the Government’s policy towards the exchange rate. San Serriffe is believed to be the only country in the world to have made its currency unit (the Corona) fully convertible into oil. At the time of writing one Corona is worth 1.56 barrels of oil. Because of this policy the currency is regularly re-valued with the result that inflation has been almost eliminated. Although this policy of “crude floating” fascinated the Treasury team, it was not felt that it could be applied in Britain because oil was a much smaller proportion of the total economy.

However, the team was enormously impressed with the scope for British exporters. The country’s apparent lack of concern about such things as delivery dates and the efficiency of plant was felt to offer huge scope to British manufacturers: it was agreed that a trade mission ought to be sent out some time next year.

San Serriffe oil production was reapportioned from March 30 from 15m barrels/day to 28.8m. tons/fortnight. At the same time the posted price (Arabian light marker equivalent) was adjusted from $11 barrel to an offshore quotation of C10.92 ton, a marginal premium over Gulf crude giving £2.34 cwt., discounting offsets. “If the position holds,” a spokesman said, “weighage should more than compensate for a slackening of interest in Venezuela.”

What are the major growth points?

Berthold Cushing, Deputy Administrator of the San Serriffe Development Corporation, discusses the economic outlook.

Programme for action

It would not be possible in a short article to describe in full the relations between the public and private sectors. On the other hand to discuss at length the projects entered into by the public sector alone would necessarily exclude much important work that is being done elsewhere.

There is therefore something of a dilemma in writing an article of this kind to know how much to put in and how much to leave out. Nevertheless, in approaching this problem I have assumed that the general reader needs a brief account of the past achievements of the San Serriffe economy and if possible some guidance about the major areas of growth which may attract overseas capital in the future.

Unfortunately it is not easy to be specific on either of these points. That there has been a great deal of development in San Serriffe is beyond question. And if my private hunch is anything to go by there is scope for plenty more. What form it will take is a good deal more difficult to say.

It might therefore be more helpful if I were to confine myself to a few brief generalisations so that the businessman arriving in Bodoni should have some idea of the problems he is likely to encounter and of the opportunities which await him.

It is, I think, important to realise that San Serriffe’s problems are not necessarily those of a West European country. I wish to stress the word “necessarily” because there are many occasions when there can be a remarkable similarity. It is one of the hazards of discussing the San Serriffe economy that undue emphasis is liable to be given to this aspect or that at the expense of the general picture as a whole.

What are the major growth points in San Serriffe? It was in an attempt to answer this question that the San Serriffe Development Corporation, of which I am Deputy Administrator, recently convened a series of conferences with interested parties both within the islands and from overseas.

There was, as the Administrator himself said, much creative thinking and-cross-fertilisation of disciplines. It would be invidious to single out individuals but one speaker in particular had a great deal of value to contribute and I am certain, looking back on it, that the conferences would have been less rewarding without his presence.

Secondly, having identified the growth points, is it possible to set down any guidelines which would be helpful to foreign investors in deciding which projects could make most use of their expertise? Clearly there are some enterprises which are best left in local hands, whereas others would certainly profit from an injection of foreign capital. It is important, I think, that a rough distinction should be made between the two categories.

This necessarily inadequate account of the situation as seen from Bodoni would be incomplete without a few words of caution. There is often a temptation to jump to conclusions, sometimes based on a wrong reading of the position but sometimes not, which cannot afterwards be easily rectified.

It is in the interest of San Serriffe and of its foreign investors that the parts should be seen as constituting a whole, for it is only in that way that progress will ultimately be made. But of one thing I am absolutely certain: given the decisions, taken at the right time, the right results will follow.

The sombre face of Enrico Pabst: the musical giant of San Serriffe. The only islander to achieve international renown, Pabst leapt to fame in the ’40s in Lisbon with his cello performance of Fugue for Cello and Crumhorn by Polenta. He subsequently quarrelled with his concert partner, Giacomo Incunabula, and some critics were taken aback when Pabst restored the crumhorn part for hillbilly mouth organ and played both melodic lines himself.

The charge of vulgarity which greeted this performance wounded him deeply and he retired in silence to San Serriffe only to re-emerge during his political exile under the Hispalis regime. He returned to the European concert halls but also developed a second musical career when he joined the rhythmic section of the Metro Ukulele All Stars. “I needed the coronas,” was his only comment.

A man scarred by his experiences, he is recorded as having made only one joke: that he played with Casals - and won. “It was tennis, Senhor. Now I shall challenge Pancho Gonzalez to play the cello.” T.R.

Spiking the cultural roots.

Tim Radford investigates a sonorous enigma.

Tourists fortunate enough to be permitted to visit the Flong settlements of San Serriffe during the summer solstice will be rewarded by the colourful spectacle of the Gallee sect stamping and shrieking in unison in the Dance of the Pied Slugs.

This traditional ritual (so unforgettably filmed by Hans Hasselblad in his seminal documentary of the ’30s) is the subject of bitter anthropological dispute. Crabtree (1967) argues that the genesis of the dance transparently lies in East African gastropod fetishism. Jonas Hoe, the ethnomusicologist, counters this thesis with the assertion that the accompanying instrument, the Grot (it looks rather like a slide bagpipe), is clearly of Pacific origin. The maverick Australian ethnographer, Mervyn Bluey, has publicly speculated that the Pied Slugs may well be a vague folk memory of witchetty grubs …

But this, according to Lino Flatbäd of the University of Uppsala in Sweden, who has made a lifelong study of the components of the distinctive San Serriffe culture, is to carry comparative ethnology too far. “I could, for instance, compare the Grot to the Tongan nose-flute, but what would that prove?” he asked as we sipped bitter-sweet swarfegas (a local liqueur scented with mangrove blossom) under the shade of the frangipanis on the western beach.

“But to speculate upon the origin of the Flongs is to miss the central fascination of San Serriffe culture. These people - all of them, colonists and indigenous, townsmen and peasants - have developed to a fine pitch the Cult of the Sonorous Enigma.

“Did you know that Mr Khrushchev (they don’t really know anything about him here, of course) has become a folk hero here? Solely on the basis of saying ‘You can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs.’ These people have a grave passion for phrases in which euphony and banality are perfectly matched: how else do you explain the Festival of the Well Made Play?”

Flatbäd sipped another swarfegas sadly. “The festival probably existed in some other form in earlier times, but everybody seems to have forgotten what it was. I believe in the early ’60s a liner stopped here to take aboard water and a British Council rep company on their way to Bombay gave an impromptu performance of The Reluctant Peer. It was received in puzzlement until after the final curtain went down and one of the passengers in the audience suddenly said loudly, “That’s what I call a Well Made Play.”

A group of Flongs in the audience immediately burst into applause, and went about for days repeating the phrase, … The longer I stay here the less I understand these people. Do you know that if an islander wants to make it clear that he will never do something he says ‘I will do it when the sociologists go away.’”

The Festival of the Well Made Play is indeed a unique event. Every second Mayday, local committees of Flongs and islanders of European extraction combine enthusiastically to mount the complete cycle of plays by William Douglas-Home in English, Caslon, and Ki-flong.

The festival begins at dawn on mayday with a procession and a battle of flowers, the cycle begins a noon prompt and ends 36 hours later with dancing in the streets. But during that 36 hours the cycle is watched with a discerning intensity unmatched even by the Japanese connoisseurs of Kabuki.

It is not certain that the context of the plays is properly understood: the enthusiasm seems to be for ritual aspects of the cycle - the Flongs, for instance, applaud wildly whenever an actor appears wearing a Harris tweed hacking jacket with a centre vent and cavalry twill trousers and a paisley cravat.

“I sometimes think,” Flatbäd told me, “that if a play didn’t open with French windows and a maid dusting the sideboard it wouldn’t be regarded as a play at all. There are some odd mistakes - somebody once performed the first scene of Ibsen’s Ghosts during the cycle and we were all quite taken in.”

Nobody can offer a convincing explanation for the popularity of the festival. Hamish McMurtrie is not concerned to try. “These island communities, they always distort and misunderstand mainland cultures because they see them out of context,” he said cheerfully. McMurtrie is chairman of the islands’ Committee with Responsibilities for the Arts. He is the son-in-law of His Excellency General Pica, but was in fact born in Orkney. A youngish, energetic polymath he has during the past four years built up a series of fringe events to accompany the Festival.

He has developed the islander’s taste for the Sonorous Enigma (on the wall of his office is a superbly crafted plaque bearing the pokerwork motto “There’s nowt so queer as folk”) but there are evidences of his concern for his work. His office is decorated by posters for the island’s first and only locally made film: a dramatised documentary about the control of infectious disease, it is called Yaws.

McMurtrie is concerned to use the festival as a key to wider access to European culture. Thus the foyer of the Cap Em opera house has been host to an exhibition by the Peruvian minimalist artist Felix de Garcia, and my visit coincided with tours by the Bodoni Brass Ensemble and the Ampersand String Quartet. Neither visit was a commercial success: the two together consumed almost half the Ministry’s modest annual budget, plus a small grant from Unesco and a larger subvention from the CIA.

McMurtrie confessed himself disappointed but perhaps, he speculates, the Home cycle itself might provide the answer. “The English culture is in some respects the dominant one. If I can persuade the CIA to help further I may arrange for translations of Agatha Christie, Arthur Wing, Pinero, and Hugh and Margaret Williams. If those are a success we could try something really daring, the sort of bold experiment you use in your own National Theatre. What would you say about a performance of Look Back in Anger in modern dress?”

Outside, on a whitewashed wall opposite McMurtrie’s office, someone had neatly charcoaled “It never rains but it pours.” In the seductive climate of the San Serriffe June, it seemed answer enough.

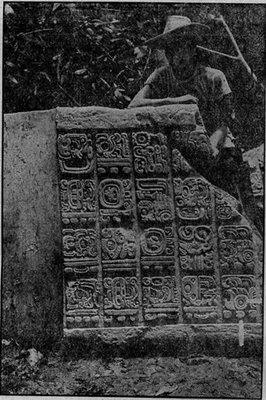

Dawn of a culture: The earliest known inscription in Ki-flong, on a stone outside M’Flong, describes “a great journey towards the sunrise.” It almost certainly refers to the slow easterly movement of the islands across the oceans, and the script, variants of which have been found in Guatemala, suggests that the territory may originally have been located off the coast of Brazil. The subsequent movement must then have been round the Cape of Good Hope.

Since the date of this inscription the written form of the language has undergone a number of modifications. The Flongs are not derived from any known African stock, but both the prefixes “Ki” (for the language) and “M” (for something of importance) appear in several African languages. It is thought that the Flong language may have been modified in relatively recent times during the transit of the islands round the African coast.

Mitred rules

by the Rt. Rev. Martin Goudy, Anglican Bishop to the Flongs

I am often asked whether the Flongs are not one of the world’s most disregarded peoples, and although standards of comparison are difficult I am forced to reply that so far the Flongs have failed to benefit from the great riches newly acquired by San Serriffe.

Doubtless it is for this reason that the Government in Bodoni discourages foreign visitors from penetrating their territory, and that in spite of the highly advanced transport network elsewhere it is rare to see any conveyance in M’Flong larger than an Audi 100LS Automatic.

“Itn goro apapawaapa, ngoro awapa” is an old saying in the Ki-flong language which I have heard times without number as the people gather in the evening at their huts: “He that smiteth shall surely himself be smitten.”

The Church has thus taken the only honest course open to it in aligning itself with the Flong Front and in supporting those claims - whether to secession from Upper Caisse or to a say in of life of the Republic commensurate with their numbers - which the Flongs have advanced with increasing urgency.

When this has been said, however, the Church equally condemns the violence with which some of the claims have been accompanied. The series of raids on tourist hotels at Cap Em and Villa Pica certainly achieved a purpose in drawing attention to the plight of the Flongs.

The raids may well have had a moral justification, and certainly they were carried out with commendable discipline. But the Church would be wrong if it did not express concern at the whole-sale taking of life as well as denounce the geographical isolation of which the Flongs have for so long been the victims.

The Flong claims are modest. They are not demanding majority rule: for one thing they are not in a majority. The overriding priority is the drainage of the Woj of Tipe which cuts off the Flongs from the outside world - and from the hope of freedom.

A somewhat understated nuance to San Serriffe culture is that some of the social issues may have been caused by hitherto overlooked linguistic aspects of the Flong language, otherwise known as Ki-Flong.

ReplyDeleteAfter uncounted hours of study, it appears there are, in fact, two distinct (if I may be so bold as to overstate the situation somewhat) yet very similar dialects of Ki-Flong, which I have termed Flong A and Flong B.

The local descriptive names are something which appear to sound like Hu Flong Pu and Hu Flong Dung, occasionally abbreviated to simply, Pu and Dung.

Thus it appears that as the islanders have come into contact with English-speaking off-islanders, they are maintaining their age-old custom of politely requesting that their conversational partners clarify which of the two dialects is being spoken at any given time. However the English contact has from time to time led to misunderstandings as to whether the clarification previously referred to is being expressed in English, or is pure Pu or pure Dung.

Naturally, due to the inescapable effects of being exposed to another culture, even written English statements are affected by the well-established habits of the islanders in their social custom of attempting to establish whether the statements are pure Pu or Dung or merely full of Pu or Dung.